In April 2021, President Biden convened a two-day summit with key government, private-sector, civil society, and international organization leaders to tackle the climate crisis. At the summit, the administration announced plans to launch a Global Climate Ambition Initiative, which will support developing countries in establishing net-zero strategies and implementing their nationally determined contributions and adaption strategies. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, who also serves as Chair of the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC); Ambassador of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Samantha Power; and U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) Acting Chief Executive Officer Dev Jagadesan and Chief Operations Officer David Marchick will be leading U.S. international efforts to support countries’ climate initiatives and investments. Several countries also announced plans to deepen their climate goals and strengthen efforts to combat the crisis.

Brazil

President Jair Bolsonaro pledged to end illegal deforestation in the country by 2030 and to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, 10 years earlier than the previous goal. Previously, Bolsonaro has criticized protections of the country’s forests and has threatened to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. Now, Brazil has asked the Biden administration to provide $1 billion to pay for the conversation efforts of the Amazon rainforest. Questions remain on Brazil’s commitment to the issue following Bolsonaro’s recent approval to cut Brazil’s environmental budget for 2021 by 24 percent from last year’s levels.

Canada

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised that, in addition to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, Canada will slash emissions 40 to 45 percent by 2030, compared with 2005 levels, a significant increase from its previous pledge of 30 percent.

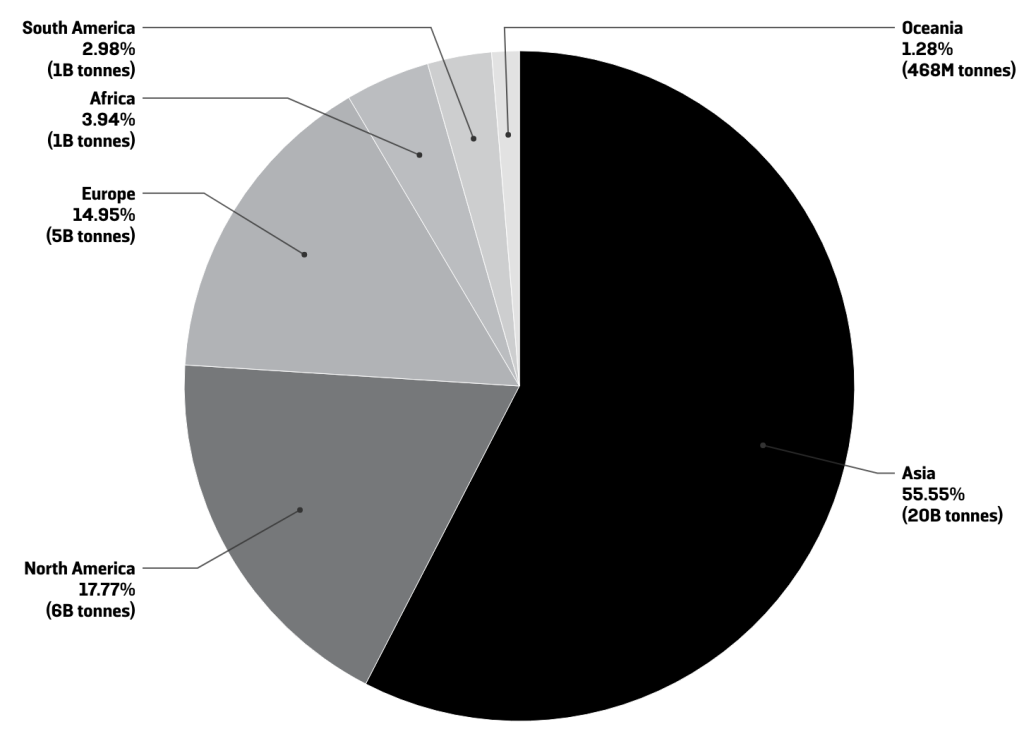

China

President Xi Jinping reaffirmed China’s commitments to reduce emissions by 60 percent before 2030 and to go carbon-neutral by 2060, adding that coal use would gradually decrease in the second half of this decade. Although China has not changed its emissions goals, Xi’s attendance signals potential for U.S.-China cooperation on cutting climate emissions.

Germany

German Chancellor Angela Merkel praised President Biden’s plans to tackle climate change, asserting that it was an important signal of the U.S. return to the negotiating table. Germany has reduced its emissions by 40 percent, compared to 1990 levels, and it has plans to continue cutting emissions as well as to contribute to the new EU target of reducing emissions by 55 percent by 2030. In January 2021, Germany notably increased its commitment to support developing countries with their climate-adaption efforts, providing an additional 220 million euros.

India

At the summit, Prime Minister Narenda Modi and President Biden launched the India-U.S. Climate and Clean Energy Agenda, which will focus on strengthening bilateral collaboration between these two countries across climate and clean energy. India is the world’s third largest emitter behind China and the U.S., and in a meeting in early April 2021, Modi reaffirmed to Kerry that the country was on track to meeting its pledges under the Paris Agreement.

Japan

Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga promised a new target, asserting that Japan will curb emissions by 46 percent by 2030, compared with 2013, levels–up from its previous commitment of 26 percent–and to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

Norway

Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg, alongside the United Kingdom and the U.S., pointed to reforestation as a key priority for the country’s efforts to combat climate change. Norway has made available high-resolution satellite imagery of tropical forests to help improve management and verify performance. It is also notably part of the Lowering Emissions by Accelerating Forest finance (LEAF) coalition, which seeks to mobilize private capital for countries that reduce deforestation.

Poland

President Andrzej Duda promised that the country will build and use zero-emissions energy systems over the next 20 years, which Duda projects will reduce the share of coal in the current system from 70 percent to 11 percent by 2040.

Russia

President Vladmir Putin said that Russia will broadly pledge to “significantly” reduce the country’s emissions in the next 30 years and that it will make a significant contribution by absorbing global carbon dioxide. Putin also proposed giving preferential treatment for foreign investment in clean energy projects and called for a global reduction of methane. President Biden has pointed to advanced technologies such as carbon removal from space as a potential area for U.S.-Russian cooperation.

South Korea

President Moon Jae In vowed that South Korea will end public financing of future coal-fired power plants overseas, which experts state may help persuade China and other coal-reliant countries to curb building and funding new ones as well. He also announced plans to increase the country’s targets to reduce emissions by 24.4 percent from 2017 levels by 2030.

The summit was the first in a series of meetings that President Biden plans on prioritizing with world leaders, including the Petersburg Climate Dialogue, Partnering for Green Growth and the Global Goals Summit, the Summit of G7 Leaders, the UN General Assembly, and COP 26 talks in Glasgow. UN Secretary-General António Guterres has pointed to 2030 as a critical deadline to prevent the “climate catastrophe,” urging that 90 percent of countries must commit to achieving net-zero emissions by the Glasgow conference in November 2021. The conference will also be a crucial moment for leaders to deliver vital climate finance commitments, particularly $100 billion to support developing countries’ climate actions, which was not met in 2020 partly because of the pandemic.